Properties and Patterns of Elegant Systems

14 Oct 2025 | 16 minutes to read

Algorithms exist within a system, and usually process one or more inputs to produce an output. These principles can be applied across all levels of computing abstraction, from hardware and software to cloud and . This post explores foundational patterns in system design that ensure algorithms and architectures are efficient, predictable, and scalable.

[流れ]

Data flows through space

Systems revel in balance

The enmeshed gates sing

- Core Principles of System Design

- Data Handling Strategies

- Scalability \& Performance Optimization

- Adaptability and Usability

- Conclusion: Building Elegant Systems

- Appendix I - Case Studies \& Practical Examples

- Appendix II - Links to More

Core Principles of System Design

Simplicity: Minimize Complexity

Avoid unnecessary features, but balance the minimalism with practicality. Systems should have a narrow scope of problems to solve. Feature and scope creep pull attention away from the central purpose of a system and introduce additional “error-surface” for bugs and issues to grow from.

Minimize the amount of stateful components in the system. If you’re storing any kind of information for any amount of time, you have a lot of tricky decisions to make about how you save, store and serve it. Stateless systems are simpler to test and verify. By pushing stateful to the edges of the system, it removes complexity from

The design should minimize edge cases in applied logic. This makes it easier to mentally model the system and reason about functionality.

Performance: Balance Efficiency & Resources

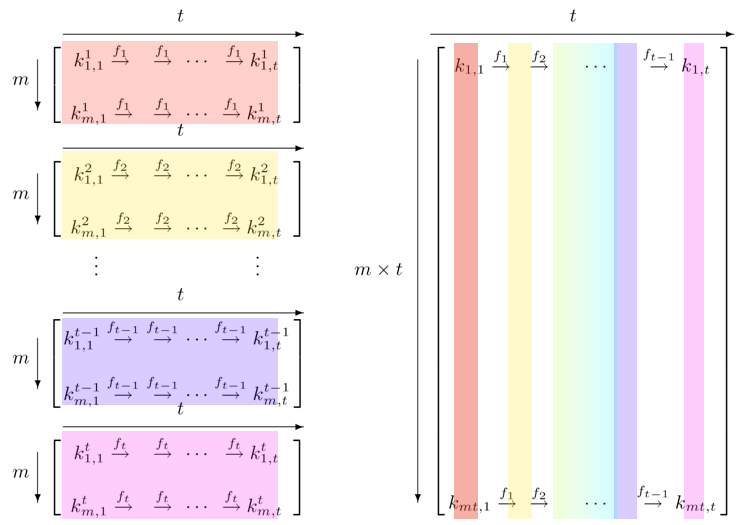

Adding more resources improves performance of a system, to a point. The various limits of hardware and software all scale differently from each other, so performance characteristics end up differing across scales of operation. Parallelism, pipelining, and serialization are common design patterns to spread work across resources. The scaling structure used should be derived from the structure and behaviors of the input data.

While compute and memory are usually the primary focus, all aspects of the system should be considered. Financial, network, disk, data speed/latency and power usage are all considerations in improving efficiency.

For best performance the system should exist in a balance of input and processing resources. There should exist slack in the system, relational to the volume and processing cost of the system input. If resources are saturated and there is a surge in input, there will be an greater impact to performance than if there are unused resources able to accommodate the additional load. In my experience across computing applications 80-85% utilization is around the sweet spot.

Predictability: Consistent Behavior Over Time

Best / Average / Worst performance of the algorithm should be similar over the range of possible inputs. To illustrate, sorting algorithms are simple to reason about.

Quick sort first partitions the array and then make two recursive calls. Merge sort first makes recursive calls for the two halves, and then merges the two sorted halves.

| Algorithm | Quicksort | Merge Sort |

|---|---|---|

| Time Complexity (Best) | O(n log n) | O(n log n) |

| Time Complexity (Average) | O(n log n) | O(n log n) |

| Time Complexity (Worst) | O(n²) | O(n log n) |

| Space Complexity (Best) | O(log n) | O(n) |

| Space Complexity (Average) | O(log n) | O(n) |

| Space Complexity (Worst) | O(n) | O(n) |

They are roughly comparable in the best and average case, there is a drastic difference on worst case performance. Algorithms may also perform differently on different scales of input data.

Despite this, a program could utilize both algorithms by detecting properties of the data before processing and using the right algorithm for the job.

While processing the data, resource usage should be stable. There shouldn’t be choppy CPU usage, and Expensive operations like memory allocation and disk/network requests should be performed up front. They should make data available to the core algorithm without hoarding CPU.

Correctness: Accuracy & Precision

Algorithms should produce accurate results under all valid inputs. They should adhere to specific constraints such as idempotency. For simple problems math, a calculator would be useless if it performed carries on a portion of the time. Problems modeled by systems need to have measurable outcomes.

Outputs derived from data should be factually correct (see LLMs) Processing the same set of data twice should result in the same output.

In sorting algorithms, there is the concept of stable vs unstable sorting algorithms. A stable algorithm will preserve the relative order of equal elements, while an unstable one may or may not shuffle the order of equal elements. While this may not matter for sorting raw values, it can be valuable when sorting data structures on a field. More entropy is introduced into the system but it is up to the goals of the system to determine if it’s relevant or not.

A concept from physical sciences is systematic error vs. random error. Systematic error is a consistent, reproducible error that stem from within the system. This error can be:

- Clock drift

- Floating-point arithmetic

- Resource contention

- Outright error (2+2=5)

- Unchecked expiration

Random error causes include instrument limitations, minor variations in measuring techniques, and environmental factors.

- Input issues/fidelity

- Security

- Upstream outages

- Weather events

- Interstellar rays

- System just didn’t feel like it

Systematic errors can mostly be solved. Because they arise from the architecture and design of the system they can more directly be confronted. Random errors can be mitigated but not eradicated. The system exists within reality, but steps can be taken to minimize and compartmentalize the error. “Swiss-hole” security allows individual layers to have failures/issues that can be covered by other layers. Of course, if the holes line up you’re gonna have a bad time.

LLMs take an interesting approach by often being incorrect and confident. From a high level, they are deterministic. Provided the same seed and a 0 temperature, any model should provide What is not deterministic is the system operating the LLM. Differences in hardware, scheduling, and parallelism can shuffle the order of operations in a non-deterministic (from our perspective) way.

Data Handling Strategies

Data Locality and Movement

Algorithm should be able to perform tasks on a subset of the data. It should not require processing all the data to get a result (processing everything required for the result).

Data should be stored in a way that’s conducive to how it will be processed. The algorithms data access patterns should integrate cleanly with how the data stored. Usually, algorithms fall into either being message or stream oriented. Data stored with random access make it easier to batch and compartmentalize work.

Algorithms that require random data access do NOT perform well with stream-oriented data sets

Memory access patterns should be optimized to minimize cache misses and maximize reuse of data in memory. Individual, discrete units of data should be processed as few times as possible, extracting what’s needed for the lifetime of the algorithm in minimal passes.

At a programming level, this could mean utilizing hash maps and dicts to group data instead of using un-indexed lists. Data storage-wise, this could mean s3 buckets with data spread across a folder tree that groups files on some valuable property.

Data Shapes and Structure

What data shapes and structures are consumed and produced

Data structures describe how data, metadata, and references are contained.

The organization of data to play to strengths of algorithm. Don’t want to over-index, or chop up data into too-fine pieces. Analogy to min-maxing surface area and volume of a square. Indexing shouldn’t be overly specific. Meaningful clustering of data.

Graph traversal is a core computing problem where storage structure can drastically reduce work. With just a raw list of nodes and edges, it can be expensive to determine paths between two nodes.

By storing the graph in a hash map, nodes can readily be hopped between. The data will be able to be explored as a graph by hash lookups rather than iterating through a list.

Having the raw data organized in a map is nice, but additional information about the data can be gathered to further improve task performance. “Regularization” of the input data can help simplify the problem you’re trying to solve.

Structure decisions control the way in which data is processed and interpreted.

Pre-Processing for Efficiency

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Predictor%E2%80%93corrector_method

Pre-processing data before it enters parts of the subsystem. Key information about the data can be extracted before the primary processing takes place to better inform and optimize the processing.

For example, the speed of a search algorithm on a list will vary wildly depending on if the list is sorted or not. Over an unsorted list, an algorithm would need to analyze each list item on it’s own. By sorting the list beforehand, the algorithm can rely on guarantees inherent in the data being processed and utilize better algorithms.

The pre-processing can take place during or outside of the algorithm’s execution lifecycle. Lookup tables are a common example of using pre-computing to improve task performance. Before computers there were used to speed up calculation of complex functions in trigonometry, logarithms, statistics and more.

Composable Across systems

Instead of solving every problem, it is better to inter-operate with other tools. The algorithm and tool that encases it should readily integrate with other applications and systems.

In the *nix world, most terminal applications are line-of-text oriented.

By following the “Unix Philosophy” of managing data as files and text streams, tools like awk, grep, cat, and find can be combined to solve a task.

Data Hierarchy and Latency Reduction Scalability

Performance should be maintained across orders of magnitude of input. The varying data sizes should be able to be handled with sacrificing efficiency (linear vs. quadratic growth).

Algorithms should have a clear model for describing how data moves through the system. It should also be aware of the transport of data as it passes through caches, buffers, networks, and physical locations.

Compute should be placed near the input data. Data should be processed near where it is stored to minimize latency side-effects.

In a cloud architecture settings, this looks like cross-AZ and cross-Region data movement. In machine code this could be optimizing data slices for L1 and L2 processor cache. Each layer from the processor doing the work is a magnitude of difference

The more copies of the data that exist makes it easier for them to become out of sync. Cache layers can solve problems, but also create potential for many more. Data Lifetimes

Scalability & Performance Optimization

System Bottlenecks and Design Avoidance

Choosing the right abstraction layer to solve problems.

Avoid system limitations through thoughtful design.

Cost Awareness: Balancing Tradeoffs

Computing costs money. Every layer of abstraction has it’s own costs and benefits.

Our capitalist system uses cost as a driver, the financial aspects are also a driver in resource decisions. With the rise of [SaaS, PaaS, *aaS] it can often be cheaper to outsource functions to achieve “good-enough” functionality in a short timeframe.

The system should optimize for cost per operation within itself. Of course, “cost” needs to be defined by the hopefully benevolent entity managing the system. Time is a large factor, not just of the operations performed but the time-effort cost of constructing, managing and deconstructing the system over it’s lifetime.

Adaptability and Usability

Able to easily adjust to changing inputs and environments.

This doesn’t need to happen “on the fly”, but the code describing the algorithm should be contained enough to be easily applied to other problems.

Many advances in science and engineering have been made by applying an old tool to a new problem. By

Layers of Levers: Configuration

Configuration is an additional way of communicating intent to the system separate from the input data.

grouped by function and breadth of changes. Is meant to abstract away complexities from the user, providing an ergonomic way to “steer the ship” Keep it simple and self-explanatory.

Minimize side affects, provide clear

Graceful Failure: Handling Errors

Errors will always happen. Even if all inputs, states and outputs are accounted for, there are factors outside of the system. Links go down, hardware fails, and cosmic rays love flipping bits. When encountering unrecoverable issues, plan for a graceful landing and exit instead of plowing a burning path of faults, errors, and corruptions.

It is often better to fail out early rather then trying to continue and create bigger issues. In databases, design patterns like transactions and Write-Ahead-Logging (WAL) help minimize erroneous writes from failing clients and servers. By taking steps to preserve state before work is done the system can guarantee (to a degree) the atomicity of actions taken.

User-facing errors should be actionable and explain what went wrong. They should communicate what the system was doing and what input was being operated on. The message should cover the “who what when where” parts of the problem, the “why” and “how” are usually left to the user to solve.

Error codes and the like are valuable as an index, but they require external resources to index against. Most systems aren’t constrained by bits and bytes so messages can be more verbose. In programming I prefer to return errors instead of exception-ing out of the main control flow. Exceptions are expensive, and forces core parts of the system to be ready to “play catch” from potentially disparate sub-systems.

Documentation & User Experience

Algorithms do not operate in a vacuum. They must be cared for and maintained like any living thing. Documentation should outline the use case for the algorithm and how to apply it.

The complexities of the system should be described in an understandable way. It should use ideas and references familiar with the target audience. Having a “system vocabulary” of concepts and modules gives users a scaffold to construct understanding upon.

There should also information on how the system fails. Users should be able to easily determine the cause of errors, and have the tools/knowledge available to solve it themselves.

Even if it is the most optimal algorithm ever constructed for a task, if it is not ergonomic to users than it will be forked or forgotten.

Conclusion: Building Elegant Systems

Everything old is new again. The questions of how to design a computing system have been asked and answered innumerable ways over the decades. Most of the problems we strive to solve are echoes of those faced by our computing progenitors. We as engineers face physical and digital constraints that design is bound to.

“Be vicariously lazy.” - Programming Perl 1991

Appendix I - Case Studies & Practical Examples

Factorio’s Pathfinding Algorithm

Factorio Friday Facts #317 - New pathfinding algorithm describes their process in developing an npc algorithm.

In path-finding algorithms, this can mean grouping nodes by location or travel cost. Group 1x1 locations into say 64x64 tiles. the algorithm can then first process the large tiles to get a rough estimate of a path, then explore more likely tiles before less likely ones resulting in less data processing overall.

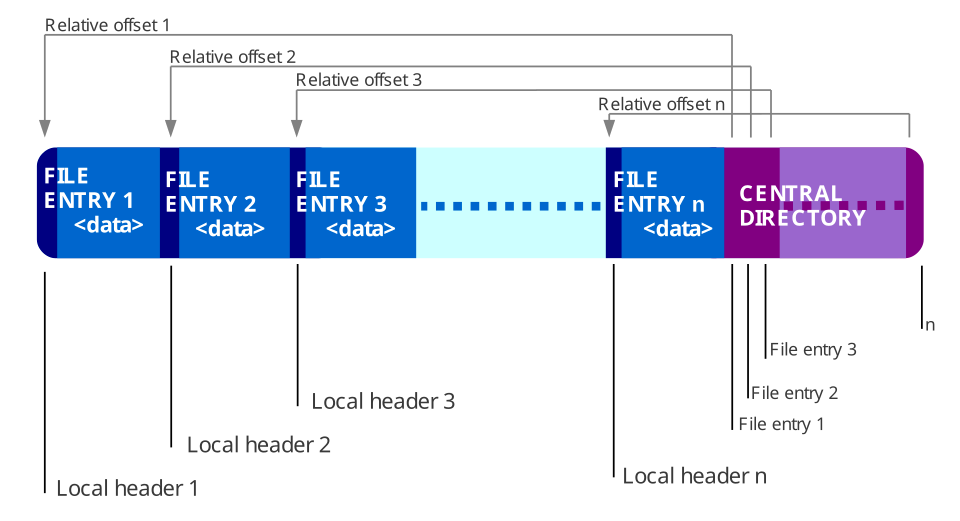

Zip-64 and Tape Storage Limitations

The ZIP-64 internal layout places the index of stored files or “General Directory” at the end of the archive structure. This is advantageous for writing a zip file, as the client only knows the data of the General Directory once all files are written. This also can ease adding files, as they can overwrite the old General directory before writing the updated one.

This structure is not helpful when attempting to read an archive. A naive implementation could require processing the entire zip file to read the General Directory and provide it to the user.

Some systems can work around this, but others have hard constraints on how data can be accessed.

High-density tape drives provide large amounts of storage, but only read data sequentially.

This makes ZIP-64 particularly bad, as the system must first seek to the end of the tape before being able to meaningfully access an archive.

Rainbow Tables in Cryptoanalysis

Rainbow Tables are pre-computed chains of password hashes.

are another, more modern form of lookup tables. They help drastically improve hash cracking performance. Instead of storing every single plaintext and hash, “chains” of hashes are created and only the ends are stored. The target hash is repeatedly hashed using the same method to create the chains. If the result matches one of the chain “ends”, the algorithm can then hash from the head of the chain to determine the input that generates the matching hash.

Appendix II - Links to More

Core Principles

Simplicity

- Simplicity of IRC - Susam Pal

- htmx sucks - Carson Gross

- Great software design looks underwhelming - Sean Goedecke

- The Architecture of Serverless Data Systems - Jack Vanlightly

Performance

- Simulating Time with Square-Root Space - Ryan Williams

- Exploring the Power of Parallelized CPU architectures - meekochii

Predicatability

Correctness

Data Handling

- Make a Faster Cryptanalytic Time-Memory TradeOff - Philippe Oechslin

- Hash-Based Improvements to A-Priori

- Regularization -

- Using Obscure Graph Theory to solve PL Problems - Sandy Maguire

- Hypergraphs, in the context of index and metadata creation.